Most people in Australia will no doubt know the name Bernie Madoff and that he was responsible for the largest Ponzi scheme in history. The prosecutors in the US estimated that the extent of the fraud was US$64.8 billion, and that it ran for more than two decades. A little closer to home, you may have read about the Queensland Finance Manager who fraudulently stole $20.7 million from his employer Leighton Contractors over a 12 year period. The story of the ‘Tahitian Price’ who recently took $16 million from Queensland Health is also well known.

While these very large frauds are reported in the mainstream media, small fraud is far more common and can have equally or even more devastating effects on its victims than its bigger brothers. While Bernie Madoff’s actions had a devastating effect on the Hedge fund he operated, and many of its investors, there was minimal disruption to the operations of Leighton Constructions and the Queensland Health Department. At the other extreme, consider the impact of an employee fraudulently misappropriating $50,000 from the local fruit and veg shop owner. Consider the consequences of an employee of a small building supply business fraudulently ordering tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of stock, and having it delivered directly to building sites and then fraudulently invoicing the builders on fake documents, with the employee’s personal banking details.

In both cases, what on face value might appear to be a small fraud, has had devastating consequences on the businesses and their owners. Both organisations, which were already struggling financially, were eventually forced out of business, causing their owners major financial and personal difficulties.

What, if anything, do all of these frauds have in common? The answer is Red Flags!

With almost every case of fraud, be it large or small there are always telltale signs or ‘Red Flags’ that should have alerted the owners, management or other stakeholders to ‘smell a rat’. I was recently engaged to investigate a fraud with a view to providing a brief of evidence to be used to prosecute the perpetrator in Court, to support the victim’s insurance claim and report to the directors so they could consider their responsibilities in terms of continuous disclosure, and how similar frauds could be avoided in the future. My investigation revealed the presence of a considerable number of red flags that should have alerted management to the fact that something was just not right.

The background

The following is loosely based on the actual matter that I was recently engaged to investigate. My client was a small listed public company that traded in a certain type of financial instruments. The perpetrator of the fraud who I will call Victor Villain (or Vic, as he was known) was your typical loyal and trustworthy senior clerk who had been working in the finance department for over ten years. Vic was known to like gambling on horses, and was often found at the local TAB at lunch time. For various reasons, Vic’s manager had agreed to let him work from home on an irregular basis, and had arranged for him to have remote access to the network. He was also given unrestricted access to the office, and would regularly work outside of normal office hours when no one else was present.

Vic’s job entailed purchasing and selling the financial instrument that the Company actively traded in. He was also responsible for reconciling the stock of the financial instruments to the statements provided by the external and independent issuer of those instruments.

The Company had, and remained to appear profitable. During the two years prior to the discovery of the fraud, the company had moved from having a quite healthy positive cash position, to a very significant borrowing owing to its parent company.

The anatomy of the fraud

In his book, Other People’s Money: A Study into Social Psychology of Embezzlement (1953) Donald R. Cressey identified the Fraud Triangle that graphically depicts the three elements that are typically present in frauds.

What had happened? Vic had been presented an opportunity to rectify a problem that he had. For a number of reasons, the main one being his gambling habit and his partner’s business suffering from the effects of a major down turn in business and aging plant and equipment, Vic had a need for a significant amount of cash. These reasons were the pressures or motivations in the triangle. The rationalisation was a sense of entitlement that Vic felt, which stemmed from a feeling that he had unduly suffered and was owed more than what he had.

The major opportunities that Vic was given came in the form of a number of failings in the company’s internal control system. A business with an appropriate and robust system of internal controls will very rarely suffer from a major fraud. A series of internal control weakness was needed for Vic to get away with fraud for the two years that it remained undetected.

Vic was responsible for buying, selling and reconciling the inventory of the financial instruments. He had been able to illegally obtain a bundle of approximately 100 pre-printed blank cheques, which he had used to issue fraudulent cheques made payable to a related party, or to third party vendors for his personal benefit.

Upon investigation, I found that the reconciliations had not been completed for a number of months and that some of the older reconciliations had been forced to balance with the statements from the issuer. I further discovered that senior management had not signed off the required reconciliations each month, despite being required to do so. Further, it was discovered that approximately 35 cheque numbers ran significantly out of sequence.

What were the red flags?

Lack of segregation of duties

The first weakness that should have been seen as a red flag by management was the fact that Vic was responsible for buying and selling the financial instruments, as well as reconciling the inventory of the instruments to the statements from the issuer. Had management been checking the reconciliations and signing off each month as required, the red flag would have been obvious. It was discovered that monthly reconciliations had not been prepared for at least the last six months, and the management was unaware these reconciliations were not being undertaken. Had management followed their own procedure of signing off the monthly reconciliation on a timely basis, they would have been aware of the missing reconciliations.

Missing cheque numbers

The second red flag that should have been detected was that a series of preprinted cheque numbers ran significantly out of sequence. What had happened here was that a series of cheques had appropriately been signed out to Vic to transport to a second office, but were not required to be signed into a register at the receiving office. Vic was able to keep about 100 preprinted cheques for himself.

He would then raise a payment to a genuine supplier of the instruments into the accounts payable system. The effect in the accounting system was to increase the stock or inventory of the instruments, and to raise a creditor that needed to be paid. Before the creditor could be released for payment, Vic accessed the accounts payable system and changed the payees name to an entity he controlled, or a third party supplier. In an attempt to cover his tracks, he would then change the name back to the correct name after the cheque was printed.

A simple review of the cheque numbers clearing the bank statement would have revealed to management that something was not right.

Weak security controls

While Vic had network access to initiate and amend a payment in the accounts payable system, he did not have the authority to print a cheque. He then proceeded to take advantage of another weaknesses in the company’s internal controls. When a new user was set up on the system, the IT Manager gave that user a log in ID consisting of the person’s first initial and their surname. He then assigned a temporary password and asked the new user to change it to their own nominated password. I discovered two more weaknesses in the company’s internal control, the first one being the IT Manager was less than diligent when he gave everyone the same temporary password, that being, ‘password’. The second issue was that the system did not prevent the ongoing reuse of the temporary password by only allowing it to be used once before it had to be changed.

Vic simply logged in using the ID for all of the employees that he knew had access to print a cheque, and tried the standard temporary password until he found one that had not bothered to change their temporary password.

Using the cover of early morning or late night access when no one was in the office to see him, another control weakness, Vic used one of his previously stolen preprinted cheques and logged in as the person whose identity he had stolen and printed the cheque. He then forged the signature of one of the authorised signatories and presented the cheque at the bank where it was duly cleared into an account controlled by Vic.

Cash versus profit

What appears obvious to me, which was clearly missed by management, was the fact that two years prior to the fraud being detected the company had a cash balance in the order of $1 million.By the time the fraud was detected, this amount had disappeared and was replaced by a significant loan account owing to the parent company of about $1 million. Given that the company remained profitable throughout this period, management should have made enquiries as to the reason for this turnaround in cash position. Again, they missed the obvious red flag.

Behaviour and lifestyle changes

Behavioural changes can include a person becoming more irritable and defensive at work, which would be caused by the stress placed on the person attempting to keep his or her fraudulent activities undetected. Excessive gambling, alcohol usage and/or drugs are often also obvious red flags.

Another red flag is a change in lifestyle of the fraud perpetrator. This can be reflected in purchases that are not supported by the person’s income such as lavish homes, boats, jewellery and expensive cars. In this case, Vic had recently acquired a new BMW which given management’s knowledge of his is income, and the fact that his partners business was under financial pressure, should have led them to wonder how he could afford this vehicle. As it turned out, one of the fraudulent cheques was made payable to a motor vehicle dealership.

Red flags that could have been identified using data analytics

The use of data analytic techniques could have identified a number of red flags, that if investigated, would have caught Vic’s fraudulent activity very early in the process and saved the business a significant amount of money.

A simple analytical tool used regularly is to review the audit trial. Had this been implemented by management, it would have been revealed that Vic’s user ID had been used to change the name and payee details of a number of valid creditors. A review of the audit trials would also have shown these changes were being made at times outside normal working hours. Both of these revelations would have led to some difficult questions being asked of Vic as to why this was happening.

Data analytical tools could also have been used to identify duplicate payment values paid to the valid creditor, as well as to Vic, and any cheque numbers being used out of sequence.

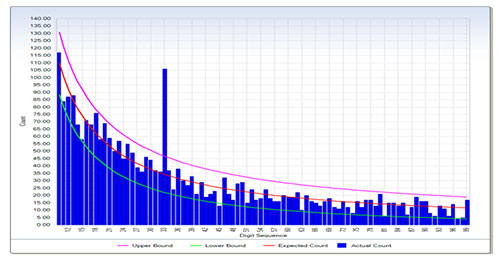

Another common and very useful analytical tool is the use of Benford’s Law. While this was not of any assistance in the investigation into Vic’s fraud, it has been of great assistance in other investigations. Benford’s Law simply states that the leading digits in any natural occurring sequences of numbers will follow a predictable pattern. The following graph demonstrates how Benford’s Law works. The graph maps the dollar value of payments made by a company over a period time to its creditors. The red line on the graph is the expected rate of occurrence predicted by Benford’s Law, while the pink and green lines represent an acceptable upper and lower deviation from the predicted norm. The horizontal axis shows the first two digits of the dollar value of each payment while the vertical axis shows the rate of occurrence.

When I investigated why the spike had occurred at 33, I discovered that a particular manager had an authority to authorise payments up to a value of $3,500. What he was doing was authorising multiple fraudulent payments just below his authorisation level. By using this tool, I was able to very efficiently and quickly target my resources to an area of higher risk instead of trolling through all or at least a large sample of data. This of course reduces the cost of investigation.

Holidays

Again, while it was not a factor in Vic’s fraud, a very common red flag is when an employee fails to take annual and/or sick leave, or even passes up the opportunity for promotion. The issue here is that employee is too scared to let anyone else take over his or her role in fear that they discover the fraud. I was recently engaged to quantify the extent of a fraud and to prepare a brief of evidence to be used in the perpetrator’s prosecution. The employee who had been with the company for many years and was considered to be loyal and trustworthy had not taken holidays or sick leave in years.

The fraud was uncovered when a relative of the employee died, and when the employee was reluctant to take time off to attend the funeral, despite his manager insisting. While he was away, another employee took a phone call that he would normally take. The phone call was from a debtor complaining that a large payment that he made had not appeared on his most recent statement. What the employee would normally have said to the debtor was that it was his mistake, and it would be rectified on next monthly statement. However, the employee would apply another debtor’s payment to the first debtor’s statement. The second debtor would subsequently ring with the same complaint. It only took one day’s absence for the fraudulent activity to be discovered.

Conclusions

What I have demonstrated in this article is the need for diligent management teams, who are able to identify the red flags that indicate the existence of fraudulent activity within their business. Managers who are prepared to invest in the appropriate data analytical procedures being performed on a regular basis can greatly reduce the impact of fraud. While having a robust system of internal controls and being conscious of the red flags alone will not prevent the occurrence of fraud, early identification will reduce the duration of the fraud, and therefore its dollar value and in the costs of investigating it.

The cost of undertaking a fraud risk control review will invariably be cheaper than the cost of an actual fraud occuring. This is particularly true when you consider the statistics indicate that in the majority of cases, recovery of cash or other assets fraudulently obtained will never be fully recovered. The other issue to remember is the damage that a fraud can have to the reputation of an organisation.

Finally – be aware the red flags of fraudulent activity and act upon them promptly.

If you would like any assistance with undertaking a fraud risk control review, please contact one of our forensics experts.

Related Articles:

ATO crackdown on lack of compliance

Personal Insolvency (bankruptcy) – most affected areas along the eastern seaboard

Australian Accountants, Lawyers & Directors Conference (AALDC)

Construction Alert: Corporations Act v Security of Payment Legislation